Deliberately creepy photo of St. Helen’s from the south. (my photo)

December 9, 2014 update: The news has gotten out that St. Helen’s and the adjoining property Stone Gables have been vacant for about three years. St. Helen’s is currently caught between the Correctional Service of Canada and the municipal government, the latter of whom wants the house’s interior heritage features to remain intact. Correctional Services doesn’t want to do this, finding such a ruling too restricting and inconvenient.

While wandering around King St. West recently, I noticed for the first time that it’s possible to access the rear lawn of St. Helen’s, the house at 440 King St. West long occupied by Corrections Canada. I was pleased and saddened and surprised all at once by what I saw: a once-grand but visibly dilapidated mansion staring out sadly towards the lake.

I was pleased because it’s a nice area to have access to and I (like many people) love nothing better than a crumbling mansion to set the tone; however, the place is literally falling apart and this is surprising considering the historical and architectural associations it has. I have no idea why it’s been left the way it is; perhaps there’s a reason I don’t know about. But St. Helen’s, or Mortonwood as it was also called, caught my imagination and I had to find out more about it.

St. Helen’s was built in 1838 for Kingston’s first mayor Thomas Kirkpatrick, the same year that Kingston was incorporated as a town and the same year Kirkpatrick assumed the office of mayor. The house was built on twelve acres of land outside Kingston’s western town limits, which at this time was the fashionable place for a gentleman of means to reside. In fact, this area of Kingston, bordered roughly by Union St. to the north, Barrie St. to the east, Lake Ontario to the south and westward to Portsmouth, still holds evidence of this development. For example, Bellevue House is located in this area, as are Summerhill and Roselawn (The Donald Gordon Centre), and a number of other smaller cottage-like homes which date to the same period.

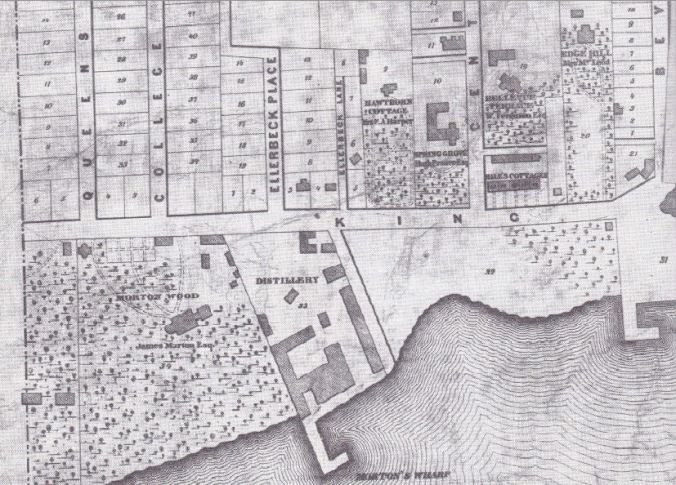

Detail of an 1865 map by John Innes showing the location of St. Helen’s (Mortonwood) and other villas. Scanned from the book “Architecture of the Picturesque in Canada,” p. 42.

Thomas Kirkpatrick came to Kingston from Ireland in 1820, became a lawyer, and in 1829 married Helen Fisher of Adolphustown, who St. Helen’s is named after. (The “saint” part was apparently intended to make the name sound grander. I agree, just plain “Helen’s” sounds like a 24-hour diner or something). However, when Kirkpatrick moved into this house outside the town limits, questions were raised as to whether by law he could still be mayor of Kingston. The council chose to appoint another mayor, and Kirkpatrick resigned. Nevertheless, he continued as a lawyer and prominent citizen who at the same time raised quite a large family. Sadly, among the children born at St. Helen’s, two of them also died: Henrietta, aged six, and later Marianne, aged twelve.

Still, St. Helen’s would have been a wonderful house for children, with twelve acres of treed grounds and a lovely waterfront. The fortunate landscaping and view were no coincidence, either. Belonging to the English “Picturesque” movement in landscaping and architecture, which emphasized integrating buildings harmoniously with their natural environment, care had been taken to give St. Helen’s full advantage of its location. As the 1857 Kingston directory described it (by which time James Morton was living there):

ST. HELEN’S, – the charming residence of James Morton, Esq., is situated on King street, fronting with a delightful slope upon the bay shore. The grounds, 12 acres, were very tastefully laid out by the former proprietor, and have been greatly and expensively improved under Mr. Morton’s well known liberal charge, and would well repay a stranger for the time necessary for a visit, where he will be sure of a hearty welcome, from Mr. Morton and his amiable lady.

All this, and running water too (really!). James Morton comes into the picture here because by mid-century he had not only added a saloon to his brewery and distillery, located just a stone’s throw to the east of St. Helen’s, but was keeping 200 cattle on the north side of King St. After a spell of bad press and another short stint as mayor, Kirkpatrick got fed up with having saloon-goers and cows for neighbours, and in the early 1850s he sold the property to Morton and built a new house on Emily St. James Morton’s ownership begins a whole new chapter in the life of St. Helen’s, or as he called it, Mortonwood.

All my photos are from the south, because I didn’t anticipate writing this post at the time! Note the crumbling stucco and broken shutter to the right. (my photo)

James Morton, like Thomas Kirkpatrick, came to Canada from Ireland at a young age. He first worked with the brewer Thomas Molson in Montreal, then apparently followed him to Kingston. In 1831, Morton started a new brewery with Robert Drummond, but upon Drummond’s death just three years later Morton took full possession of the enterprise. He later added a distillery to the premises, which as you know were right beside Mortonwood.

Also like Kirkpatrick, Morton became a very busy man in Kingston, although in business schemes. Throughout the 1850s he bought real estate, went into shipping, took over a pre-existing ship engine firm and began the Kingston Locomotive Works (a.k.a. Ontario Foundry), which was later called the Canadian Locomotive Company and remained in operation until the 1950s.

Morton also helped build the Kingston section of the Grand Trunk Railway, but a subsequent bad railway deal which coincided with the 1857 economic depression left him in a tight spot. He was a very friendly man, apparently a little too friendly with his money, and he had become somewhat out-of-step with the changing industrial economy. By 1859 he was in a great deal of debt. Incidentally, this didn’t stop his home from becoming the chosen location for the Prince of Wales’ (later King Edward VII) stay in Kingston on his 1860 tour – although because of Orange Order trouble the Prince never actually set foot in town. Eventually, however, Morton was forced to lease his distillery to bank trustees, and the furniture at Mortonwood was auctioned. When he died on July 7, 1864, as M.L. Magill wrote, “he did not even own the bed in which he died.”

Mortonwood was then sold to Robert M. Barrow, a captain, who added the porte cochère to the north entrance of the building, complementing the monumental portico on the south side which was added by Morton. However, Barrow died sometime before 1883, and I don’t know what happened until Edward J.B. Pense, owner of the British Whig, bought the property in 1907 and named it Ongwanada. Under his ownership, an extra storey with oriel windows was built over the west wing, under plans by architect William Newlands.

The extra storey is really quite seamless. “Oriel” is a term for a bay window that appears only on an upper storey. (my photo)

After the First World War, the Canadian government leased St. Helen’s (which was given back its original name) as a hospital for returned soldiers, along with the adjoining brewery property. In 1919 the government decided to buy it, and it served as the district military headquarters until 1968. I assume after this point, Corrections Canada took over St. Helen’s. So there you have it: one house, so many stories! (Unintentional pun.)

But this makes me feel worse about its deteriorating condition. True, stucco can be repaired, shutters fixed, and the rotting verandah replaced. None of these problems necessarily suggest structural instability. But St. Helen’s should have been maintained better. For example, it has been recognized in the Canadian Register of Historic Places, administered by Parks Canada, as “one of the finest examples of Picturesque Regency architecture in Canada.” Its Heritage Character Statement also emphasizes its “[e]xcellent craftsmanship and detailing” and suggests that “extreme care should be taken in its future management.”

This sentiment was echoed by M.L. Magill in his (her?) article in Historic Kingston on James Morton, calling St. Helen’s “one of the finest surviving houses in the City,” and Janet Wright’s Parks Canada report Architecture of the Picturesque in Canada similarly considers it “one of the finest products of the retreat into the suburbs which became the fashionable practice for wealthy Kingstonians during the 1830s.” With its architectural sophistication and astonishing amount of history, I think St. Helen’s deserves more respect than what its current state suggests.

St. Helen’s has seen better days. (my photo)

Sources

Angus, Margaret. The Old Stones of Kingston. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966.

Angus, Margaret. “Thomas Kirkpatrick.” Historic Kingston 38 (1990).

Canadian Register of Historic Places: St. Helen’s

Christie, Peter. “What’s in a Name?” The Whig-Standard. May 11, 1991. http://search.proquest.com/docview/353289090?accountid=6180.

Magill, M.L. “James Morton of Kingston – Brewer.” Historic Kingston 21 (1973).

Wright, Janet. Architecture of the Picturesque in Canada. Hull, QC: Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Supply and Services Canada, 1984.

If the property were restored to its former glory I wonder if it could be run as an historic site much like Bellevue House. Or as a venue for events such as weddings, conferences and the like. Maybe Queen’s will buy it!